As we enter what feels like day seven thousand and four of “lockdown”, I hope everyone reading this is doing as well as can be expected, in the circumstances. While everyone else is (according to the broadsheet press) baking sourdough bread, learning Sanskrit or perfecting their Hammond organ technique, I thought it would be as good a time as any to revive crime.scot. I have started adding new pages to the “guide to criminal law” sections of the website, and will keep doing so for the foreseeable future.

By now, the seismic impact of COVID-19 will be apparent to anyone reading this. It has disrupted day to day life in the in a manner that almost few living people can relate to. It has forced the most right-wing UK government for generations to embrace what appears to be economic socialism. And, of course, it has caused thousands upon thousands of deaths, many of which may not be reflected in the official statistics. Those confined to (and working in) care homes and prisons are at an intolerably high risk of infection. In respect of the latter, kudos to @ThePrisonLawyer and others on Twitter for standing up for people who might otherwise be completely voiceless.

From a legal perspective, business as usual in the court system has almost entirely stopped (which is terrific news if you’re on the verge of calling as a self-employed advocate, having earned nothing since last September BUT I DIGRESS). Both civil and criminal cases are being adjourned well into the future, in the hope that life will have returned to some semblance of normality by then.

Notwithstanding that, the criminal courts cannot stop entirely. If they did, there could be no prosecution of “new” cases, which society would obviously not accept. People will still commit serious crimes (indeed, there are well-founded fears of a spike in instances of domestic violence), the police will still arrest them, and COPFS will (mostly) still prosecute them. In that vein, lawyers and court staff still working to keep custody courts running, despite the inherent risks to their health and safety, deserve the same respect and gratitude that we rightly afford to NHS staff.

The Coronavirus (Scotland) Act 2020 came into force on 7th April 2020. It covers certain matters that are devolved to the Scottish Parliament. As my focus on this site is criminal law, I thought it might be useful to have a look at the more interesting provisions of the 2020 Act (“the Act”), and the associated Health Protection (Coronavirus) (Restrictions) (Scotland) Regulations 2020 (“the Regulations”), insofar as they relate to crime. Due to the length of the topic, I’ll start with the Act today, and cover the Regulations in a separate post very soon.

So, what does the Act mean for criminal justice in Scotland?

Duration

It is important to note from the outset that both the Act and the Regulations are intended to be temporary. s12(1) of the 2020 Act states that the main provisions of the Act will expire on 30th September 2020. That said, s12(3) immediately allows the time limit to be extended by up to twelve months (so, to September 2021) if the Scottish Ministers direct it. s13 allows the Scottish Ministers to bring forward the expiry date of any provision of the Act.

Attending Criminal Courts

One of the most significant changes to the running of the criminal courts (albeit one that is not specifically provided for in the Act or Regulations) is the consolidation of court business (first appearances from custody and first appearances on an undertaking) into ten Sheriff Courts across the six sheriffdoms of the country. Not good news if you are a defence solicitor based in Oban, since Oban cases are now to be heard in Kilmarnock Sheriff Court, 115 miles away.

Schedule 4, paragraph 2 of the Act suspends the requirement for a person (presumably including accused, witnesses, jurors and lawyers) to “physically attend a court or tribunal” unless the court specifically directs them to attend, which makes sense given what we know about the nature of COVID-19 transmission. The rest of the paragraph allows for such people to appear by “electronic means” (e.g. video link).

Fiscal Fines

Schedule 4, paragraph 7 of the Act effectively increases the ceiling for fiscal fines as an alternative to prosecution. Where the limit was previously £300, it is now £500.

This can only be in order to discourage court proceedings, in favour of “getting rid” of cases by offering the accused person the chance to buy their way out of prosecution. By increasing the fiscal fine limit, more types of cases can be dealt with in this way. Most court-imposed fines are below £500, in my experience.

I take no pleasure in saying that this is one provision to keep an eye on, once life goes back to normal. Criminal defence lawyers have long been suspicious of what is perceived as gradual shifts by government towards cheaper and cheaper ways of dealing with crime. Prosecuting someone is relatively expensive, whereas issuing a conditional fixed penalty is not.

The public should be wary of the long-term impact of more and more crimes being dealt with on an administrative basis, without having evidence tested in court. Once a measure is in place, and has been “proven effective”, then it is politically convenient to simply have it become the new normal. You are probably already aware of the Scottish Government’s attempts to temporarily do away with jury trials, and the widespread concerns over the long-term implications of doing so. The public do not necessarily win if criminals are not prosecuted.

Time Limits

Schedule 4, paragraph 10 of the Act essentially deals with the disruption to ordinary court business by increasing the time limits that are designed to prevent delay in trials.

Ordinarily, if bail is refused and an accused person is remanded in custody while awaiting trial, the amount of time that they can be held on remand depends on whether it is a solemn or summary case. In summary cases, the trial must start within 40 days of the remand. In solemn cases, an indictment must be served on the accused within 80 days of the remand, a preliminary hearing (or First Diet) must be held within 110 days of the remand, and the trial must start within 140 days of the remand. These limits also apply if an accused person is detained in hospital so that a mental health assessment or treatment order can be carried out.

The Act adds a six month “suspension period” to the above time periods for solemn cases, and a three month “suspension period” for summary cases. In other words, accused people remanded in custody (or detained in hospital) will now be deprived of their liberty for much longer. Bear in mind that the country has only been “in lockdown” for about three weeks. Six months is a very long time when you’re sitting in jail, particularly when you have nowhere to go to escape a potentially deadly virus.

The Act also increases the time limit for commencing proceedings for certain summary cases (e.g. various offences under the Road Traffic Act 1988) from six months to twelve months. It also allows the court to adjourn a case for sentence for as long as it considers appropriate, where it would ordinarily be up to eight weeks “on cause shown”.

Hearsay

(note to self: do a page on hearsay)

This is the “trial by statement” part that you might have heard of. Generally, witnesses need to come to court and give evidence of what they personally saw or heard. Normally, it is not good enough for a prosecutor to hand the judge / jury a copy of a statement that an absent witness gave to the police a long time ago, and say “that’s their evidence”, because that would be hearsay. The Scottish justice system quite rightly places a great deal of weight on the decision-maker being able to see and hear a witness in the witness box.

That said, remember how nobody has to physically attend court unless specifically directed to? Schedule 4, paragraph 11 of the Act provides that the risk of coronavirus (either to the witness’ own health, or the risk that they would transmit it to others) is a good enough reason to allow a written statement to be admitted as hearsay evidence. There are already certain scenarios in which hearsay evidence is admissible (e.g. where the witness has died since giving the statement), so this paragraph just adds a coronavirus-specific reason to the list that already exists.

This is another area in which the public should be vigilant once life returns to normal. A perfectly coherent statement on paper can easily fall apart once a witness is in the box and being cross-examined. Hearsay removes the opportunity for either side (or the judge) to ask questions or test the evidence in any way. In my experience, judges and juries are fairly reluctant to give hearsay evidence much weight when assessing the strength of the Crown case, but I suspect that that is mainly because it is the exception to the standard practice of having a witness speak to their experience, on oath, from the witness box. We should all be wary of attempts to do away with witnesses giving evidence in court, as difficult as it may be at times.

Community Payback Orders

Where a Community Payback Order with an unpaid work (or other activity) requirement has been imposed on a convicted person, Schedule 4, paragraph 12 of the Act extends the time period for completion by a blanket 12 months.

Early release of prisoners?

Schedule 4, paragraph 19 gives the Scottish Ministers the power to release certain prisoners early. I should note immediately that, at the time of writing, this power has not been used, to my knowledge.

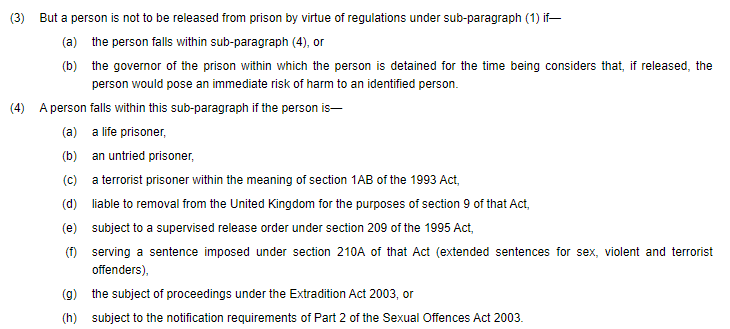

Paragraphs 19(3) and (4) specify types of prisoners who would not be eligible for early release, such as life prisoners, “terrorist prisoners”, those on remand and anyone whom the prison governor would pose “an immediate risk of harm to an identified person”.

So far, one prisoner has died from coronavirus. As with any death in custody, this will trigger an automatic Fatal Accident Inquiry in due course. It is in nobody’s interests for prisoners and prison staff (around a quarter of whom are already off sick) to die in prisons, and for Fatal Accident Inquiry after Fatal Accident Inquiry to conclude that prison deaths were avoidable. Clearly, you cannot just open the prison gates, but hopefully appropriate regulations will be in place shortly. Not every prisoner deserves to die behind bars, and no prison staff deserve to be exposed to such a heightened level of risk.

In Part 2 (coming soon): is gin a “basic necessity”? Can you sit on a park bench without fear of arrest? Can you go out just because your children are REALLY annoying you?

Do you think that Bitch, Carole Baskin, killed her husband?

LikeLike

Hi Joe – big fan (although I’d rather you hadn’t shot those tigers). I am available for instruction in extradition proceedings if she ever decides to come to Scotland. Can’t offer an opinion beyond that, unfortunately.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting stuff. Thanks. Is there a danger that in the end we move towards doing deals in the American style to keep people out of court because it’s cheaper? Or have I been watching too many U.S. dramas?

LikeLike

Thanks for the post. Once this is over, do you think there is a danger that we will see more deals done to keep people out of court to save money in the American style? Or have I been watching too many U.S. crime dramas?

LikeLike